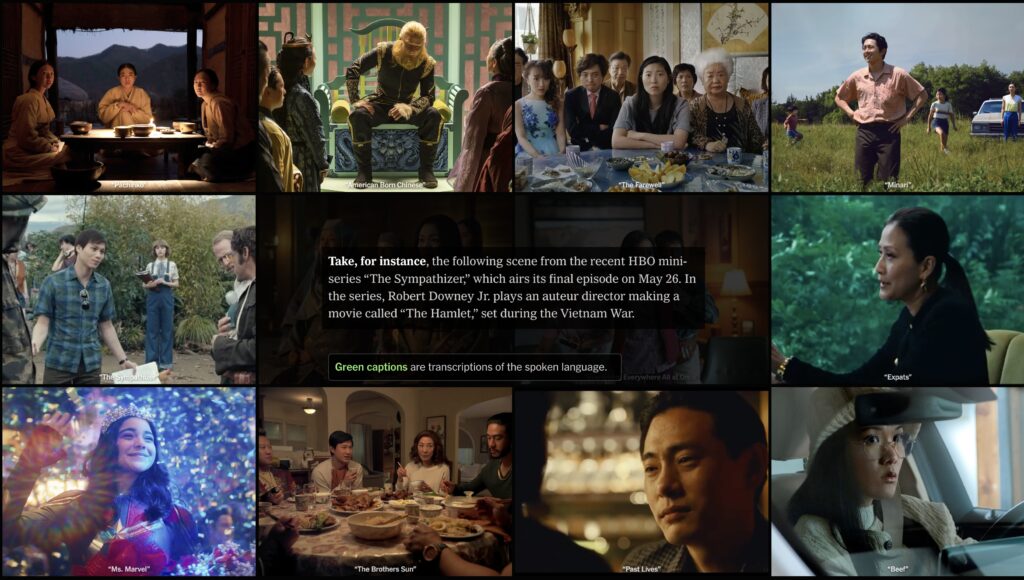

In the US, we have been hearing about an Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation (title of a report released in 2023 by the Surgeon General at that time, Vivek Murthy). A 2024 Harvard study on Loneliness in America found that 21% of adults in the U.S. feel lonely, with many respondents feeling disconnected from friends, family, and/or the world. This is not unique to the US, as there are ministers of loneliness in Japan and the UK. It is also not a new phenomenon. In 2000 Robert Putnam published the best seller, Bowling alone, which described the loss of community in the US, especially the decline in membership in civic associations and religious groups. This week, there was an interesting interview on this topic on NPR (Fresh Air) with Derek Thompson, the author of a recent article in The Atlantic, entitled The anti-social century. In that article Thompson writes that “Americans are spending less time with other people than in any other period for which we have trustworthy data, going back to 1965… Self-imposed solitude might just be the most important social fact of the 21st century in America.” While this continues the trend described in Putnam’s book, Thompson sees its growth in part due to the Corona pandemic. He cites, for example, the fact that in the US in 2023, 74 percent of all restaurant traffic came from takeout and delivery, rather than dining in, a development clearly accelerated by the pandemic.

In the US, we have been hearing about an Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation (title of a report released in 2023 by the Surgeon General at that time, Vivek Murthy). A 2024 Harvard study on Loneliness in America found that 21% of adults in the U.S. feel lonely, with many respondents feeling disconnected from friends, family, and/or the world. This is not unique to the US, as there are ministers of loneliness in Japan and the UK. It is also not a new phenomenon. In 2000 Robert Putnam published the best seller, Bowling alone, which described the loss of community in the US, especially the decline in membership in civic associations and religious groups. This week, there was an interesting interview on this topic on NPR (Fresh Air) with Derek Thompson, the author of a recent article in The Atlantic, entitled The anti-social century. In that article Thompson writes that “Americans are spending less time with other people than in any other period for which we have trustworthy data, going back to 1965… Self-imposed solitude might just be the most important social fact of the 21st century in America.” While this continues the trend described in Putnam’s book, Thompson sees its growth in part due to the Corona pandemic. He cites, for example, the fact that in the US in 2023, 74 percent of all restaurant traffic came from takeout and delivery, rather than dining in, a development clearly accelerated by the pandemic.

Another cause he cites, and discussed in the Harvard study as well, is technology, i.e. the use of smart phones and social media, a topic addressed in Sherry Turkle’s book, Alone Together, and regularly lamented in mainstream media. People (across the world) are spending time they used to share in person with family and friends now glued to their smartphones watching short videos and engaging in shallow text exchanges. Attention spans have become short and long-form reading has declined (as my colleagues often lament), a phenomenon discussed in the bestseller by Nicolas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains. Thompson argues (in the NPR interview), however, that in some cases the online world has deepened relationships, for example, the opportunity to stay continuously connected throughout the day by texting: “So the inner ring of intimacy has grown stronger, or it’s potentially grown stronger for some people, in this age of the smartphone”. At the same time, the Internet provides the opportunity for “networks of shared affinities”, the chance to build community across widely distributed groups based on shared interests.

Loneliness can lead to depression and an unhealthy cycle of withdrawal from social contact, something we as human beings are genetically conditioned to experience. There are also societal and political consequences, according to Thompson. He argues that there is an important social layer that is being left behind, that is situated in between the intimate group of close friends and family and the more distant (mostly) online affinity groups: “The inner ring of intimacy is strengthening, and the outer ring of tribe is also strengthening, there’s a middle ring of what he [Marc Dunkelman, a researcher at Brown University] calls the village that is atrophying. And the village are our neighbors, the people who live around us.” According to Thompson, we have increasingly socially isolated ourselves from our neighbors, particularly when our neighbors disagree with us. Interestingly, he connects this to the rise of political populism:

We’re not used to talking to people outside of our family that we disagree with, and this has consequences on both sides. On – for the Republican side, I think it’s led to the popularization of candidates like Donald Trump, who essentially are a kind of all-tribe, no-village avatar. He thrives in outgroup animosity. He thrives in alienating the outsider and making it seem like politics, and America itself, is just a constant us-versus-them struggle. So I think that the anti-social century has clearly fed the Trump phenomenon.

Thompson points out the media have accelerated this process (as I have discussed), with people increasingly only accessing media outlets that carry points of view they agree with, further reinforcing the echo chamber of the “tribe” we belong to. Thompson’s solution?

To connect all of this back to the anti-social century, we all need to get out a little bit more. And if we want to be appropriate and wise consumers of news, we want to be wise consumers of news that make us sometimes feel a little bit uncomfortable about the future…I do recognize there’s a collective action problem here to solve. But I also think it’s really important not to overcomplicate this by suggesting that requires some enormous cultural shifts. I think that our little decisions, the little minute-to-minute decisions that we make about spending time with other people, these decisions can scale. They create patterns of behavior. And patterns of behavior create cultural norms.

So in the end he offers a bit of hope, that increases in individual social connections (including beyond our comfort level) can have positive societal repercussions.

Or maybe we will be going in the opposite direction, establishing connections not with our fellow citizens but with an AI lover (Yikes!). Or maybe connecting with robots? As being tried out in Japan.