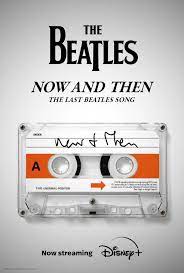

I’m in Vietnam currently, giving workshops on using AI tools in teaching English. Yesterday, we looked at what ChatGPT, Bard, and Bing might suggest as “best practices in using AI in language learning and teaching”. One of the suggestions was using AI chats as “authentic” language practice. That has set me to wonder what that word means in the context of AI text generation. That topic has been raised this month with the release of a new Beatles song, a musical group that disbanded over 50 years ago, with only 2 of the 4 members still living. A recent article in the New York Times discussed the issues related to that release:

I’m in Vietnam currently, giving workshops on using AI tools in teaching English. Yesterday, we looked at what ChatGPT, Bard, and Bing might suggest as “best practices in using AI in language learning and teaching”. One of the suggestions was using AI chats as “authentic” language practice. That has set me to wonder what that word means in the context of AI text generation. That topic has been raised this month with the release of a new Beatles song, a musical group that disbanded over 50 years ago, with only 2 of the 4 members still living. A recent article in the New York Times discussed the issues related to that release:

Does it really make sense to use a song originally written by [John] Lennon alone, with no known intention of ever bringing it to his former bandmates, as the basis for a “Beatles” song? Is Lennon’s vocal, plucked and scrubbed by artificial intelligence and taking on a faintly unnatural air, something he would have embraced or been repulsed by? “Is this something we shouldn’t do?” McCartney asks in a voice-over, but neither he nor anyone else ever articulates exactly what the problem might be. “We’ve all played on it,” McCartney says. “So it is a genuine Beatle recording.” On one hand, who is more qualified than McCartney to issue this edict of authenticity? On the other: Why did he feel the need?

The author makes the point that this is quite different from what we all have been worrying about with AI, namely brand new “fakes”. In this case it is an example of using tech advances to, in the author’s opinion, make money from recycling old material:

The worry is that, for the companies that shape so much of our cultural life, A.I. will function first and foremost as a way to keep pushing out recycled goods rather than investing in innovations and experiments from people who don’t yet have a well-known back catalog to capitalize on. I hope I am wrong. Maybe “Now and Then” is just a blip, a one-off — less a harbinger of things to come than the marking of a limit. But I suspect that, in this late project, the always-innovative Beatles are once again ahead of their time.

The question of authenticity has one that is at the core of the communicative approach to language learning, with the idea that learners should not be working with made-up, simplified language materials, but be provided with real-world materials that native speakers would themselves might be accessing. For the materials to be comprehensible, learners are supplied with “scaffolding” (annotations, notes, glossaries, etc.). Online materials have been a boon in that respect, in contrast to most materials in textbooks. Now, AI is making the question of authenticity and attribution much trickier. AI generated materials are not products of native speakers, so should we treat them, as we do manufactured texts as lacking in authenticity? Certainly, the cultural perspective is missing, which is one of the principal benefits of using “authentic” materials. Stay tuned, as AI and attitudes towards its output are evolving rapidly.