Are we trying too hard to educate our children? Yes, we’re trying to do too many things and most are not helping. That’s in part the conclusion of Amanda Ripley who wrote a book on education throughout the world entitled, The Smartest Kids in the World: And How They Got That Way., whose work was profiled today on NPR. As is often the case when comparing educational systems, schools in Korea and Finland draw much of the attention, given the higher scores school children there achieve on standardized tests. As I’ve written in a previous post, the schools in Finland are a riddle for American educators who go to visit and learn – how can they do so well without all the solutions being advocated in the U.S. : school choice (more private and charter schools), rewards for the best teachers and schools, high-stakes testing to identify success and failure. Instead, Finland focuses on turning out excellent teachers, paying them well, offering a lot of local support, and encouraging the best college students to go into teaching: a few important things done well.

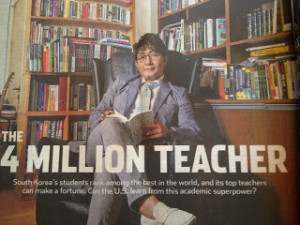

South Korea is quite different, with a heavy emphasis by all stakeholders on children focusing on high achievement, even if that means long hours after school and on weekends in private tutoring sessions. Earlier this month there was a profile in the Wall Street Journal of an English teacher in South Korea who makes millions of dollars a year through his subscription video service and after-school tutoring sessions. The Korean educational system could hardly serve as a model for the U.S., but American foreign language teachers would be happy to see that kind of pay. In the end, we all know it comes down to the quality and commitment of teachers – the trick is to figure out how we become more successful in filling our schools with dedicated and competent teachers and in ensuring they receive reasonable pay, support, and respect.