This week the statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, Virginia, (just down the highway from me in Richmond, VA, the capital of the Confederacy) was melted down, to be later transformed into a new statue of some kind, likely representing ideas and beliefs very different from those Lee’s statue represented. The statue was built during the Jim Crow era and was designed to champion the “lost cause,” the claim that the cause of the Confederate States in the Civil War was just, heroic, and not about maintaining slavery in the South (which it was). An article in the New York Times puts the Confederate monuments (many of which were here in Richmond until recent times) into context:

Confederate monuments bear what the anthropological theorist Michael Taussig would call a public secret: something that is privately known but collectively denied. It does no good to simply reveal the secret — in this case, to tell people that most of the Confederate monuments were erected not at the end of the Civil War, to honor those who fought, but at the height of Jim Crow, to entrench a system of racial hierarchy. That’s already part of their appeal. Dr. Taussig has argued that public secrets don’t lose their power unless they are transformed in a manner that does justice to the scale of the secret. He compares the process to desecration. How can you expect people to stop believing in their gods without providing some other way of making sense of this world and our future?

There has been a lot of discussion about the Confederate statues since 2017, when the Alt-right marches happened in Charlottesville (in large part to protest the planned removal of the Lee statue) and even more since 2020 and the murder of George Floyd. Some have argued the statues should be kept as a historical record, perhaps with more in-place context provided (information on the origins and intended meaning of the statues). The NY Times article argues that the fate of the Lee statue was appropriate, given that no possible recontextualization or relocation (to a museum) would please everyone and that the original statues were erected with great fanfare:

That’s why the idea to melt Lee down, as violent as it might initially seem, struck me as so apt. Confederate monuments went up with rich, emotional ceremonies that created historical memory and solidified group identity. The way we remove them should be just as emotional, striking and memorable. Instead of quietly tucking statues away, we can use monuments one final time to bind ourselves together into new communities.

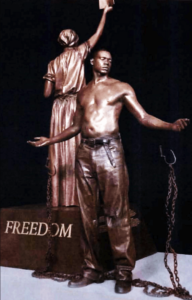

The city of Charlottesville has awarded the remains of the Lee statue to The Jefferson School African American Heritage Center, which leads Swords Into Plowshares, a project that will turn bronze ingots made from the molten Lee into a new piece of public artwork to be displayed in Charlottesville.

.