The American Civil War Center

A new museum has opened up recently here in Richmond, Virginia, namely the American Civil War Museum, located in the former Tredegar Iron Works, along the James River. The new institution is a merger of two museums: the long-standing Museum of the Confederacy and the American Civil War Center at Historic Tredegar. The museum is striking, dug into the Tredegar hillside, with a glass curtain as an entrance. Upon entering, visitors pass through ruins of the Tredegar Iron Works before reaching the museum proper. The take on the Civil War is equally striking. Rather than serving as a shrine to the Confederacy, as one might expect in the city that served as the capital of that break-away entity, the museum strives to tell a balanced and broad history, one that includes narratives from the variety of participants: Union and Confederate, soldiers and civilians, women and children, enslaved and free African-Americans. There is no attempt to provide a single perspective, but rather to mirror the diversity of experiences. According to the architect responsible, Damon Pearson, that idea is built into the building design: “The exhibits themselves are meant to be fragmented. We tried to reinforce that with the architecture. You’re meant to see this event from as many different viewpoints as possible. And you’re seeing all of them simultaneously” (interview in the Richmond Times Dispatch).

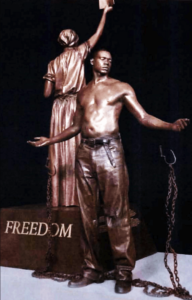

One of the crucial aspects of the museum artifacts is that they are shown and documented in context, with rich information on their provenance and on the people involved. That’s in contrast to the famous (or infamous) Confederate statues along Monument Avenue in Richmond (of Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, and other Confederate war heroes), which are shown larger-than-life, sitting defiantly on their horses, inviting the admiration of viewers who must assume, given the statues’ size and prominence (on a famous avenue), that these were indeed great historical figures. Of course, the reality is more nuanced, as these were the men fighting to maintain slavery, the real issue of the Civil War, as the new museum makes clear. What particularly is missing in viewing the Monument Avenue statues in their current stand-alone status (a small name plaque provides basic info), is the fact that they were built during the Jim Crow era, as a manifestation of the belief in the Confederate “lost cause” narrative, i.e. that the Confederacy was a just cause and that the South was in its rights to secede (and to maintain slavery). In other words, the statues are a monument to white supremacy. Without the historical context, that is not immediately evident. Monuments have such a profound influence on the narratives that shape personal and group identities that we need to have as much historical context as possible to provide story lines that accord with historical reality.

One of the ways that context could be provided in viewing historical or culturally significant sites would be to use mobile technology through augmented reality. A mobile app could provide an overlay of information when a viewer points a mobile phone at a statue or other artifact. That is being done today often for tourists with apps such as wikitude, which uses image recognition technologies that allow for viewed images (through the phone’s camera) to trigger the display of localized information. That approach is being used today in Miami to provide context about climate change to murals in the Wynwood district of the city, famous for its many murals.

That might offer as well be an option in the reconstruction of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris after the horrific fire last month. There have been a variety of fanciful suggestions for re-imagining the roof and spire of the Cathedral. However, the French Senate recently passed a resolution to rebuild the Cathedral the way it was, to the extent possible. The creative re-workings of the Cathedral, if not present in reality, could be available virtually through an augmented reality overlay. That could include not only striking visualizations of Notre Dame’s roof (the spire as a beacon into space) but also historical info, such as the role of Victor Hugo’s novel (The Hunchback of Notre Dame) in exerting public pressure to preserve the valuable cultural heritage the Cathedral represents.

Two weeks ago, here in Richmond, Virginia, the huge statue of Robert E. Lee on Monument Avenue was removed. It was the last symbol of the Southern Confederacy remaining on a street which once was lined with tributes to the heroes of that cause. The statues, erected during the Jim Crow South, celebrated the “Lost Cause”, the idea that the Civil War was fought over states’ rights and not slavery and that slavery was a benevolent institution. Those reminders of the fight to maintain human slavery started to come down last summer, in the wake of the movement centered around the murder of George Floyd.

Two weeks ago, here in Richmond, Virginia, the huge statue of Robert E. Lee on Monument Avenue was removed. It was the last symbol of the Southern Confederacy remaining on a street which once was lined with tributes to the heroes of that cause. The statues, erected during the Jim Crow South, celebrated the “Lost Cause”, the idea that the Civil War was fought over states’ rights and not slavery and that slavery was a benevolent institution. Those reminders of the fight to maintain human slavery started to come down last summer, in the wake of the movement centered around the murder of George Floyd.