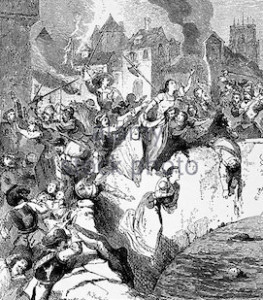

For anyone who has studied German history, mention of the capital city of the German state of Saxony-Anhalt brings to mind its significant history. Founded by Charlemagne in 805 as Magadoburg, it was one of the largest cities in the time of the Holy Roman Empire, a member of the Hanseatic League, and the city where young Martin Luther went to school. Under Luther’s influence, the city sided with the Protestants in the 30 Years War, leading to the event known as the the sack of Magdeburg, the massacre in which Imperial troops ravaged the city; out of 30,000, only 5,000 survived. By the time of the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, the city’s population stood at 450. In the 20th century, the city suffered another disaster, being almost totally destroyed in the course of World War II. Adding insult to injury, the city found itself on the wrong side of the dividing line after the war, becoming part of the Soviet occupation zone, then incorporated into communist East Germany.

The latest disaster? This past Sunday, when the extremist Alternative for Germany party (AfD – “Alternative für Deutschland”) won 24% of the vote in the election for the Landtag, the regional parliament for Saxony-Anhalt, which meets in Magdeburg. It came in second to the Christian Democratic Union (29%). While that fact has been widely reported (and lamented), what is less well known is that if one were to add in the votes for smaller, right-wing parties such as the NPD (the neonazi party which is currently under threat to be outlawed) winning 2%, the “Free Voters” (a highly nationalistic party) at 2%, the “Alliance for Progress and Renewal” (a splinter group of the AfD) at 1%, and other smaller parties such as the scary “Die Rechte”, the percentage of far-right leaning groups is likely higher than for any other party. Unfortunately, the rise of the AfD is not limited to this state, they did well in other state elections on Sunday as well. This is the party that is strongly anti-immigrant, anti-EU, and generally anti-establishment. While the general consensus (see the Economist’s analysis) seems to be that the election results are not disastrous for Chancellor Merkel or for Germany generally, it’s worrisome for anyone familiar with the history of the Weimar Republic to see such movements gain significant popular support. Of course, Germany is not the only country seeing xenophobic, populist politics on the rise. The primary elections today in several large states in the US might help determine if the US sees a similar trend prevail in one of its major political parties.