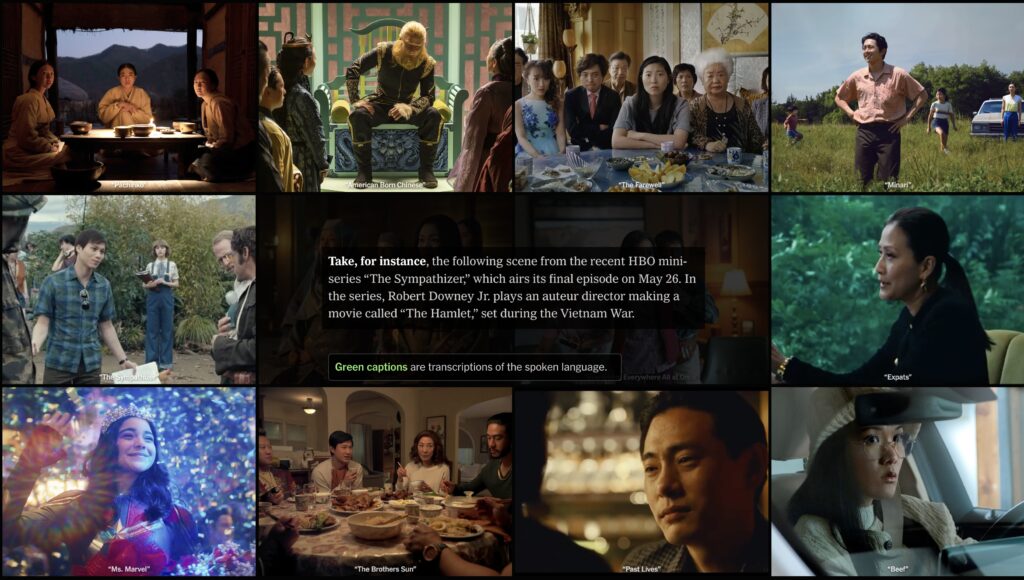

The New York Times announced recently a new series that examines the output of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) in popular culture. The first piece in the series, “Found in Translation: Asian Languages Onscreen,” is focused on the use of Asian languages in US American movies and TV. The article itself is quite interesting, but particularly effective is its online presentation, which features an innovative visual design by Alice Fang. The article points out that traditionally US movie viewers have been averse to reading subtitles but that has changed recently in respect to Hollywood movies with Asian characters. Recent hit movies Shogun and Everything Everywhere All at Once feature dialog, respectively, in Japanese and Chinese, mixed in with English.

The Web version of the article shows in interactive format how in a scene from the recent HBO mini-series The Sympathizer, a movie about making a movie, there is a kind of hidden dialog going on through the subtitles that illuminates what is happening on screen. The movie is set in Vietnam, but in that scene an actress who is playing a Vietnamese peasant speaks Cantonese. According to the article:

A crew member sheepishly explains to the director that they didn’t bother casting a Vietnamese speaker since “there’s no line in the script.” Eventually, another actress who does speak Vietnamese is brought in, and they reshoot the scene. Instead of the line the director suggests — “Don’t shoot me, I’m only a peasant” — the actress shouts one fed to her by the Captain, the on-set cultural consultant who is actually a Communist spy: “Our hands will close around the throat of American imperialism!” The swap goes over the director’s head, but for the viewer, who can read the subtitles (and for anyone who speaks Vietnamese), the layers of language become a narrative tool for political satire.

The article points out that this trend is likely to continue, as it seems to play well with audiences, adding a welcome tone of realism to movies about Asian characters that in the past were highly Americanized. For audience members who actually speak the language used in the film, the meaning is deepened, giving those viewers a special, inside track on what’s going on. The article points out that Internet users, through exposure to multilingual videos in YouTube, TikTok, etc. have grown more accoustomed and accepting of subtitles. In movies, adding authentic language enhances the story line: “Multiplicity of language is most interesting when it’s used to progress these stories — to ratchet up tension, to encase or reveal secrets, to create emotional resonance, to reflect or deflect identity.” That’s the case, for example, in the rich code-switching in Everything Everywhere All at Once which often features characters mixing Chinese and English in the same sentence. Subtitles not only enrich movies, they are also a wonderful (and entertaining) way to learn or maintain a foreign language. The fact that English language TV programs have long been shown in Scandinavia in English with subtitles has been shown to be a major factor in the citizens of those countries speaking better English than in countries such as Germany, that has always dubbed foreign video into German.

Interesting in terms of language in movies, a recent trailer has stirred a good deal of comment on accents used. The upcoming movie is the sequel Gladiators 2, which features Denzel Washington. The issue with many viewers of the trailer is that Washington does not adhere to the cinematic tradition of actors in movies about ancient Rome using British English but instead speaks in his regular New York accented American English. It’s a rather strange criticism in that ancient Romans certainly did not speak English of any kind. As many have pointed out, the Roman Empire was multicultural and therefore likely had many speakers with different accents speaking Latin. So criticizing the movie for mixed English accents is way off base.