Few of us are likely to regret the passing of the plague year 2020 (see the comprehensive New Yorker piece on the catastrophic handling of the COVID-19 virus in the US). Just a few thoughts here on the last day of the year on what has changed in our lives.

1) Human lives

My grandmother died in the 1918 “Spanish flu”. That had a profound effect on my father’s life, growing up without a mother, forming habits, tastes, personality traits that surely would have been different had his mother not died. I’m sure it contributed to my grandfather being taciturn and withdrawn. My Dad had trouble expressing emotion, as did many men of his generation, and was rather coarse in his habits (eating, for example) and abrupt in his dealings with others. No one can tell if having had a mother would have made a difference, but it seems like it could have. In turn, I see many aspects of my father mirrored in my own personality, and likely passed on to my children, and now, quite possibly to my grandchildren.

One death and many ripple effects. In the US we are approaching 350, 000 dead from the virus, many more world-wide. Unbelievable real-life repercussions on lives and families everywhere. Grieving now and long, long-term effects.

2) Cultural practices

For friends and families losing loved ones: So sad not to be able to say good-bye in normal and meaningful ways and to engage in rituals that can be tremendously meaningful to many. It seems likely that end of life practices will slowly come back, but for other culture-related practices changes may be longer-lasting.

Handshakes, hugs, standing close to others: They have disappeared this year. Will they come back or is physical distancing of one kind or another here to stay? Will it be different depending on the culture? In some parts of the world, the adjustment may not be a big deal, but if you’re used to cheek kissing as a normal greeting ritual, that’s a big change. Elbow bumps don’t seem like a satisfactory replacement.

Work cultures seem certain to have changed. Many more folks likely to continue to work remotely. That in turn brings changes to everyday lives, more time at home, more options for cooking, gardening, other homebody activities, maybe more pets?

Changes in education are equally profound. Distance learning is not likely to go away. But just as in employment opportunities, this trend will not affect us all equally. The divide between those with white collar jobs, able to work from home, and those in the service sectors, exposed to the virus, has led in the US to disproportionally high number of black and brown infected and dead Americans. Similarly, well-off parents can afford the better computing set-up and higher-speed Internet crucial to effective online learning. Those are some of the many ways the virus has brought into sharper contrast the stark inequalities in US society.

3) Trust in science (and in each other)

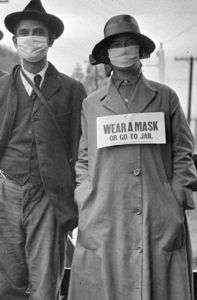

Another dividing line in the US (and elsewhere) has been the extent to which individuals have changed their public behavior to protect themselves and others from the spread of the virus. That has exposed the extent to which many people deny the findings of science and medicine (i.e., masks work) and show blind faith in voices of leaders and media figures, with no science expertise, but with plentiful political goals. Those skeptical of science, or even of the reality of the virus, have shown that they are not reachable through objective, factual information. Their beliefs in areas related to the virus have become part and parcel of their identities, of their personal life histories, and thus are nearly impossible to dislodge by logic or by any other means.

Sad to say, it seems unlikely that 2021 will bring meaningful change in that area.