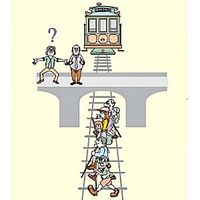

Having just completed a book chapter on culture, language learning, and technology, I was intrigued by this past week’s episode of On the Media, which replayed a story I had missed from the spring, related to how using a second language can affect decision making and moral choices. The story was based on an article in PLoS One entitled “Your Morals depend on Language” by researchers from Spain and the U.S. The authors proposed to examine the wide-spread assumption that moral judgments about right and wrong are the “result of deep, thoughtful principles and should therefore be consistent and unaffected by irrelevant aspects of a moral dilemma. For instance, as long as one understands a moral dilemma, its resolution should not depend on whether it is presented in a native language or in a foreign language.” What they found was quite different. Using several different experiments they found that using a second language resulted in more dispassionate, utilitarian decision making. They used, for example, the well-known “trolley problem” – if you could save 5 people by sacrificing one (throwing a fat man over a bridge to stop a runaway trolley), would you do it. Typically only 18% of those presented with the dilemma sacrifice the man; but for those considering the problem in a foreign language, 44% were ready to throw the man off the bridge. Through this and other experiments, the researchers concluded that using a second language provides a helpful psychological and emotional distance to a difficult decision such as a moral dilemma.

Having just completed a book chapter on culture, language learning, and technology, I was intrigued by this past week’s episode of On the Media, which replayed a story I had missed from the spring, related to how using a second language can affect decision making and moral choices. The story was based on an article in PLoS One entitled “Your Morals depend on Language” by researchers from Spain and the U.S. The authors proposed to examine the wide-spread assumption that moral judgments about right and wrong are the “result of deep, thoughtful principles and should therefore be consistent and unaffected by irrelevant aspects of a moral dilemma. For instance, as long as one understands a moral dilemma, its resolution should not depend on whether it is presented in a native language or in a foreign language.” What they found was quite different. Using several different experiments they found that using a second language resulted in more dispassionate, utilitarian decision making. They used, for example, the well-known “trolley problem” – if you could save 5 people by sacrificing one (throwing a fat man over a bridge to stop a runaway trolley), would you do it. Typically only 18% of those presented with the dilemma sacrifice the man; but for those considering the problem in a foreign language, 44% were ready to throw the man off the bridge. Through this and other experiments, the researchers concluded that using a second language provides a helpful psychological and emotional distance to a difficult decision such as a moral dilemma.

An article in Scientific American reporting on the piece on PLoS One speculates that there may be cultural ramifications to the results: “Using a native language plausibly induces the feeling that one is reasoning about in-group members. Conversely, a foreign language could signal that the scenario is relevant to strangers, foreigners, or out-group members.” In fact, studies have been done which show different responses if it is implied that the people in danger are of a different ethnicity. Another question the study raises is that of bilinguals – do they decide differently depending on language used. This question was discussed in the interview from On the Media, with the researchers having found that with true bilinguals there was no distinction, with the assumption that the emotional resonance of the trolley dilemma is the same in both languages.

The idea that different languages can call up different emotional responses is consistent with what second language teachers experience in the classroom. Learning and using swear words in a foreign language, for example, can be tricky from a cultural perspective. The visceral reaction to certain naughty words does not normally carry over to a new language, thus making it likely to use them inappropriately. Linguists know that playing with language – experimenting with how to use new vocabulary or constructing nonsense sentences – can be quite helpful in acquiring a second language. One of the other findings of the study was that users of a foreign language increased their willingness to takes risks. This can in itself be helpful in language learning, i.e. trying out language combinations not used before. The study showed, however, it can also have a not so positive result – an inclination to gamble.