Human beings are social animals. That makes social distancing very difficult, the practice of keeping ones distance from others in order to slow the spread of disease, in this case, the COVID-19 pandemic. Each one of us is of course different in terms of sociability but it’s likely that almost everyone needs some degree of regular social contact. That can come through being together person-to-person individually or in groups with friends, family members, classmates, co-workers, club members, etc. Often language will play a major role in our connections with others, in that one of its major functions is to negotiate social relations. Non-verbal communication too plays an important role in relating to others. With the arrival of COVID-19 pandemic, we still have language (more and more mediated electronically) but we have largely lost personal contact, while non-verbal behaviors have changed significantly.

It will be interesting to see what happens in the aftermath of the pandemic, whether social conventions, work arrangements, and educational delivery systems will experience long-term changes, i.e. more folks working remotely, increased use of online learning, and shifts in behaviors involving such phenomena as greetings and physical interactions. Will social distancing become engrained behavior, by default keeping our personal distance from others greater than has been the social norm in the past? Will we no longer go into automatic handshaking mode in particular situations, such as meeting someone new? If the pandemic were short-term, or likely to be a once in a lifetime event, one would not expect such changes, but neither seems to be the case. Instead of weeks, the pandemic looks like it will play out for months, maybe longer, and may be with us as a recurring event. Nor is it likely the last coronavirus we will see.

One might suspect that cultures labeled “collectivistic” would have a harder time with social distancing, given communal orientations. However, cultures generally associated with that label, namely China and South Korea, have been quite successful in fighting the virus. Keeping to cultural stereotypes, one might argue that, in fact, the willingness of individuals to forego direct social contact is in line with expectations, in that they are sacrificing in the name of the greater social good, namely slowing the spread of the virus. A recent piece in the Atlantic magazine discusses the cultural difficulties many Americans have in adjusting to social distancing. The argument is that “America’s individualistic framework is deeply unsuited to coping with an infectious pandemic”. The author, Meghan O’Rourke, asserts that the North American cultural frame of self-reliance makes it more difficult for individuals to consider the common good. Similarly, the cultural theme of individual freedom of action runs counter to the need for the restriction of movement through self-quarantining. She points out that the mania for individual responsibility has resulted in the US in a lack of universal health-care system and a weak social safety net, situations which are likely to make it more difficult to deal with the pandemic and its economic aftermath. She finds it unlikely, that the pandemic will bring a change “from an individual-first to a communitarian ethos”.

One should always approach broad-brush cultural characterizations with caution. That’s called for here, as the US is culturally very diverse, with significant regional, ethnic, and socio-economic differences, despite the undoubted presence historically of the themes of freedom and individualism in the US. It may be that the pandemic will bring about different mindsets and behaviors. It seems clear at this point that not everyone will weather the storm under the same conditions. While in some professions, work at home is doable, that’s not the case for many jobs, typically low-wage work. In an opinion piece for CNN, a group of sociologists from UCLA discuss the need to offer help to those in that position:

We must be particularly supportive of those among us who are vulnerable to contagion — unable to “physically distance”– precisely because of the work they do. This includes not only health care workers but also service and delivery workers, domestic and home care workers, cashiers, sanitation workers, janitors, store clerks, farm workers, and food servers who quietly but vitally sustain our collective lifestyles, even in a pandemic.

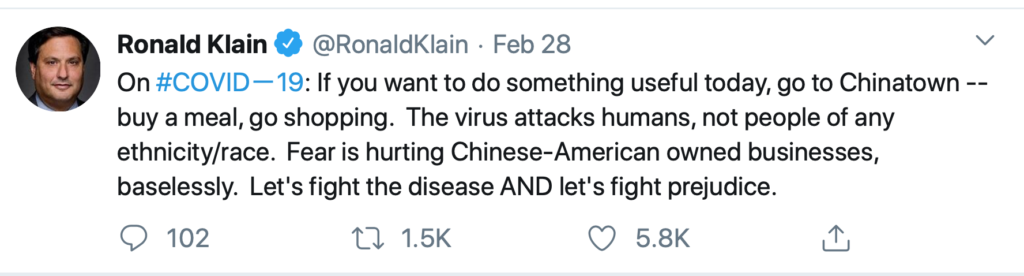

These are jobs for which the workers cannot afford to be absent from work, cannot work remotely, and often do not have health insurance. In parts of the US, those workers are likely to be immigrants, already suffering from discrimination and unequal treatment. The authors urge that instead of using the term “social distancing” we refer to “physical distancing” to encourage the practice of maintaining physical spacing, but not being distant socially. That involves practicing solidarity with those suffering more from the pandemic, as well as using technology to maintain social connections. In the process, they write, “Just as physical distancing can give us a fighting chance of combating this virus, finding creative and socially responsible ways to connect in crisis can have positive and long-lasting effects on our communities.” So long-term changes may be on the horizon; we’ll see.