History is not an abstraction: past events shape our culture and our view of others. That’s why it’s so important to get history right. Made-up history can be as damaging as made-up science.

An episode from the NPR radio show On the Media, The worst thing we’ve ever done, that was broadcast this week (originally aired in June) seemed quite appropriate for this time of the end of the year, when we take stock of the past. It was an interesting comparison of how a shameful period in a nation’s history has been viewed by later generations. The contrast was between Germany and its Nazi period and the USA and slavery. The report pointed to how many public reminders there are in Germany of the Holocaust and how it is extensively present in education and in the public sphere generally. An interview with Peter Weissenburger, journalist for the Berlin taz was enlightening in that regard. He talked about how ubiquitous the presence of the Nazi past was for him growing up, in school and in the media. For him, German identity is defined by Nazi Germany, something that can never be “resolved” so that it belongs to the past: “There’s no point in which we can say, ‘ok, we’re done now.’ This is always going to be what happened.”

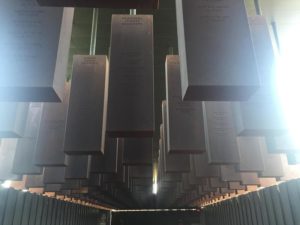

In contrast, the period of slavery and the following violence and discrimination against African-Americans is far less known in the US, or acknowledged as a problematic period in US history. According to the report, many US citizens believe that in fact slaves were treated well and are skeptical that lynchings took place (despite numerous photos and other documentation). Indeed, there are monuments to well-known slave holders and heroes of the Confederacy, which defended the institution of slavery. The report discusses initiatives to bring to the public’s attention the crimes and injustice associated with slavery and its aftermath. In Montgomery, Alabama, the first capital of the Confederacy, there are two monuments to that past, the Legacy Museum, and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. As seen from the photos above, the massive hanging steel columns in the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, each dedicated to a lynching in a particular US county, is impressive and haunting, similar to the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin. However, the project takes a step further, in an effort to bring home to local communities the reality of racist actions in the past. It is inviting communities where lynchings occurred to claim their histories in a tangible way:

The memorial is more than a static monument. In the six-acre park surrounding the memorial is a field of identical monuments, waiting to be claimed and installed in the counties they represent. Over time, the national memorial will serve as a report on which parts of the country have confronted the truth of this terror and which have not. (Monument’s web site).

The current embrace by some of “alternative facts” has led to the questioning of widely accepted scientific findings, in areas such as climate change and pollution. Pseudo-science is used to justify political views and further entrenched economic interests. History too can be retold, refused, or re-focused to accommodate political or ideological positions. The Nazis used pseudo-history to legitimize their power, presenting themselves as continuing ancient heroic Germanic traditions. Just as we need to learn from history, so as not to repeat it, we need to recognize how history and science can be distorted to support group interests.