A recent article in the NY Times discussed the influence that Kazakhstan’s first and only president, Nursultan A. Nazarbayev, has had on the development of a new alphabet for the Kazakh language, which is currently written using a modified version of Cyrillic. Nazarbayev announced in May that the Russian alphabet would be replaced by a new script based on the Latin alphabet. However, there is a problem with representing some sounds in Kazakh. The President has decided, according to the article, “to ignore the advice of specialists and announce a system that uses apostrophes to designate Kazakh sounds that don’t exist in other languages written in the standard Latin script. The Republic of Kazakhstan, for example, will be written in Kazakh as Qazaqstan Respy’bli’kasy.” Apparently, linguists had recommended that the new system follow Turkish, which uses umlauts and other phonetic markers, not apostrophes, but the President has insisted on his system. According to the article, this has led to intense debate in the country, with the President’s views being widely mocked:

A recent article in the NY Times discussed the influence that Kazakhstan’s first and only president, Nursultan A. Nazarbayev, has had on the development of a new alphabet for the Kazakh language, which is currently written using a modified version of Cyrillic. Nazarbayev announced in May that the Russian alphabet would be replaced by a new script based on the Latin alphabet. However, there is a problem with representing some sounds in Kazakh. The President has decided, according to the article, “to ignore the advice of specialists and announce a system that uses apostrophes to designate Kazakh sounds that don’t exist in other languages written in the standard Latin script. The Republic of Kazakhstan, for example, will be written in Kazakh as Qazaqstan Respy’bli’kasy.” Apparently, linguists had recommended that the new system follow Turkish, which uses umlauts and other phonetic markers, not apostrophes, but the President has insisted on his system. According to the article, this has led to intense debate in the country, with the President’s views being widely mocked:

“Nobody knows where he got this terrible idea from,” said Timur Kocaoglu, a professor of international relations and Turkish studies at Michigan State, who visited Kazakhstan last year. “Kazakh intellectuals are all laughing and asking: How can you read anything written like this?” The proposed script, he said, “makes your eyes hurt.”

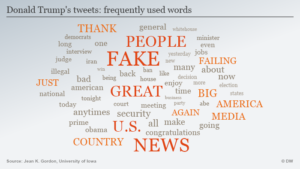

Another President, Donald Trump, has made waves with his use of language as well, as in his re-interpretation of “fake news” to mean any reporting critical of him or his actions, his use of vulgar language to describe African countries, or his habit of using insults and abusive language in his tweets. In an interview with the Deutsche Welle recently, well-known linguist, George Lakoff, commented on Trump’s use of language. Lakoff laments how the wide-spread reporting of the President’s tweets tends to cite the texts. According to Lakoff, just having that language repeated – even if within an article attacking what was said in the tweet – tends, through repetition, to plant Trump’s ideas in our heads. He points out that this is the strategy used by Russia propagandists and the Islamic State in their online messaging. The twitter bots used by Russian hackers repeat tweets over and over again, with slightly different texts, but always using hashtags that support divisiveness in the US population and electorate. This was done in the 2016 election, and is continuing, as in the recent bots’ activity in spreading the #releasethememo hashtag, in reference to the controversial classified memo that some Republicans say shows bias in the FBI’s Trump-Russian probe. This is in an effort to discredit both the FBI and the investigation into the Russian electoral interference, in the desire to undermine the US people’s faith in their government, and thus weaken US democracy.

Lakoff’s advice to the media on reporting on Trump tweets:

Don’t retweet him and don’t use the language he uses. Use the language that conveys the truth. Truths are complicated. And seasoned reporters in every news outlet know that truths have the following structure: They have a history, a certain structure and if it is an important truth, there is a moral reason why it is important. And you need to tell what that moral reason is, with all its moral consequences. That is what a truth is.

He’s not advocating stopping news reports on the tweets, but rather to put them into a proper context, and point to factual discrepancies, when they exist – and in the reporting, to forego inadvertently spreading messaging through textual repetitions. The way that politicians use language can make a big difference in how policies and actions are viewed by the public, especially if a term is repeated frequently. We are seeing that currently in the US in relation to immigration. Trump and Republicans use the term “chain migration“, which has negative connotations rather than the term preferred by Democrats, “family reunification”, which makes the process sound much more positive.