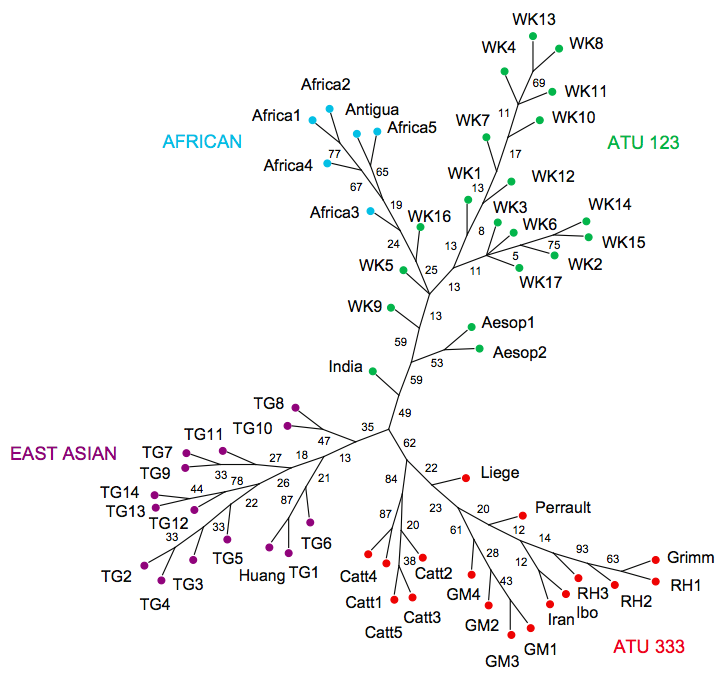

Through a note in the current issue of The Smithsonian, I was alerted to an article I missed when published last fall in the open access journal Plos One. “The Phylogeny of Little Red Riding Hood” by Jamshid Tehrani examines the origins of the well-known story, likely most familiar from the Grimm Brothers version, “Rotkäppchen”, first published in 1812 in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen. Folklore scholars have long been interested in tracing the origins of folk tales, their evolution over time, and their geographical distribution. Traditionally, this has been done through a historical-geographic methodology, best represented by the Aarne-Uther-Thompson (ATU) index, which identifies more than two thousand international types distributed across three hundred cultures worldwide. Tehrani’s approach is quite different, borrowing techniques and tools from evolutionary biology. The article details his use of phylogenetic analysis, using cladistics, Bayesian inference and NeighborNet. These methods employ a branching model of evolution that clusters characteristics on the basis of shared derived (i.e., evolutionarily novel) traits. The NeighborNet tree is shown below.

Through a note in the current issue of The Smithsonian, I was alerted to an article I missed when published last fall in the open access journal Plos One. “The Phylogeny of Little Red Riding Hood” by Jamshid Tehrani examines the origins of the well-known story, likely most familiar from the Grimm Brothers version, “Rotkäppchen”, first published in 1812 in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen. Folklore scholars have long been interested in tracing the origins of folk tales, their evolution over time, and their geographical distribution. Traditionally, this has been done through a historical-geographic methodology, best represented by the Aarne-Uther-Thompson (ATU) index, which identifies more than two thousand international types distributed across three hundred cultures worldwide. Tehrani’s approach is quite different, borrowing techniques and tools from evolutionary biology. The article details his use of phylogenetic analysis, using cladistics, Bayesian inference and NeighborNet. These methods employ a branching model of evolution that clusters characteristics on the basis of shared derived (i.e., evolutionarily novel) traits. The NeighborNet tree is shown below.

Tehrani analyzed 58 written versions of the story taken from a variety of countries over 2000 years, comparing 72 different plot points and resulting in a family tree showing the most likely relationships. One of the main findings is that, contrary to some theories, the story most likely did not originate in China (it’s not at the base of the tree), despite similar versions of the story recorded there. Unfortunately, he was able to use only tales that had been translated into English.

The sophisticated data analysis used here is not surprising when dealing with scientific topics, but may seem unusual when applied to fairy tales. However, such techniques have been used recently in other areas, including languages and manuscript traditions. In linguistics, the best-known case may be its use in mapping the origins and spread of Indo-European. Tehranie wrote about his research in The Atlantic, explaining in layman’s terms his approach. He concludes by expanding the value of his work beyond insights into origins and varieties of folk tales:

Folktales, more than any other type of story, embody our shared fantasies, fears and experiences. Understanding which elements of them remain stable and which ones change as they get transmitted across generations and societies can therefore provide a unique window into universal and variable aspects of the human condition. As such, they represent a potentially rich point of contact between anthropologists, folklorists, literary scholars, biologists and cognitive scientists.