A recent piece in the online magazine, Undark, Scientists Probe an Enduring Question: Can Language Shape Perception?, examines an interesting, new approach to the topic of linguistic relativity, i.e. the extent to which the language we speak influences how we see the world. It starts with a familiar topic within the scholarly debate around this question, namely whether the existence or absence of words for specific colors in a language affects speakers’ perception of colors. This was famously studied by Benjamin Whorf, the very same of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which first laid out this strong connection between language and culture. Whorf studied Native American languages and noted that Navaho speakers split black into two colors and lumped blue and green together into one, thus providing a slightly different color lens on the world than English. Later scholars had doubts, such as Berlin and Kay (1969), who argued that there are cross-linguistic regularities in the encoding of color such that a small number of basic color terms emerge in most languages and that these patterns stem ultimately from biology. This was put forward as evidence against the linguistic relativity hypothesis. Other researchers went further, labeling Whorf’s views as “vaporous mysticism” (Black, 1954),

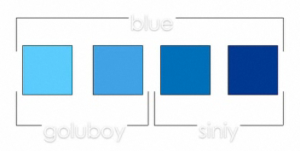

In this piece in Undark, the example centers on the color blue, and the distinction between shades of blue made in Greek (and in other languages as well) with a separate word, ghalazio, for light blue (akin to goluboy in Russian) and ble for darker blue (siniy in Russian). Instead of the usual procedure in experiments of this kind, the researchers involved (at Bangor University) did not show the participant colors and ask them to name them. Instead, they attached electrodes to their scalps in order to track changes in electrical signals in the brain’s visual system as they looked at different colors. This allowed researchers to observe directly neural activity. In the experiment, native speakers of English and Greek were shown a series of circles or squares of different shades of blues and green. Electrical activity measured in the participants revealed that in the Greek speakers, the visual system responded differently to ghalazio and ble shapes, a change not seen in the English speakers. Thus, for the English speakers everything was “blue”, while the Greeks see the world in a more differentiated way, at least in references to things bluish.

The research team decided to replicate the experiment, this time with shapes:

The Spanish word taza encompasses both cups and mugs, whereas English distinguishes between the two. When Spanish and English speakers were presented with pictures of a cup, mug, or bowl, the difference between the cup and mug elicited greater electrical activity in the brains of English speakers than in Spanish speakers.

Such experiments from cognitive scientists seem likely to continue – and to continue the debate around linguistic relativity. They do seem to provide scientific evidence that our brains are wired by language, at least in some areas. It would be interesting to see experiments of related phenomena, such as the presence or absence of grammatical genders in languages. As Guy Deutscher described in the NY Times Magazine a few years ago, psychologists have compared associative characteristics of objects with different noun genders in different languages (such as the feminine word for bridge in German, die Brücke with the masculine el puente in Spanish):

When speakers were asked to grade various objects on a range of characteristics, Spanish speakers deemed bridges, clocks and violins to have more “manly properties” like strength, but Germans tended to think of them as more slender or elegant. With objects like mountains or chairs, which are “he” in German but “she” in Spanish, the effect was reversed.

Another area of interest would be time perception, as discussed in a recent article in Popular Science, “The language you speak changes your perception of time”:

Different languages frame time differently. Swedish and English speakers, for example, tend to think of time in terms of distance—what a long day, we say. Time becomes an expanse one has to traverse. Spanish and Greek speakers, on the other hand, tend to think of time in terms of volume—what a full day, they exclaim. Time becomes a container to be filled.

The article cites a study in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, in which Spanish and Swedish speakers were asked to estimate time based in either distance (how long a line took to grow) or volume (how long it took for a container to fill). The results showed that there were indeed clear differences in the two groups in how they measured time in terms of length or volume, in other words, that the language they spoke affected how they estimated the relative passage of time. The original article, not surprisingly, is full of cautions and caveats. That is likely to be the case in such studies and provides a rationale for cognitive scientists to continue their efforts to measure brain activity related to language and culture.